Distinguished Professional Achievement Alumni Award recognizes alumni who have distinguished themselves as significant contributors to their professions, who stand above their peers, and who are recognized within their professions as role models for future generations of citizen leaders.

Historic preservation is all about the present for alumna known for her leadership of Preservation Virginia

One sunny day in 1967, an 8-year-old girl stood with her grandmother on the bank of the James River and looked out over the area that America’s first British colonists named Jamestown. Missing from the view was James Fort—believed to have been lost due to erosion from the river—the first structures built after the settlers arrived and encompassing a storehouse, a church and a number of houses. The grandmother, who loved history, talked with her young granddaughter about 1607 and the arrival of Capt. John Smith, remarking wistfully, “Imagine what we could learn if the original Jamestowne settlement hadn’t been lost.”

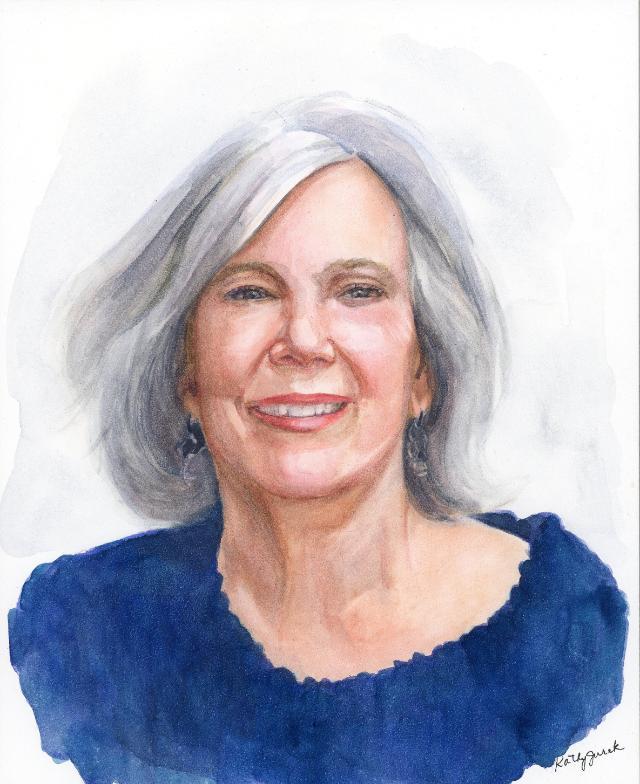

Elizabeth Stanton Kostelny ’81 vividly remembers that day with her grandmother and how oddly prescient it was.

Nearly 25 years later, in 1990, she would join the staff at Preservation Virginia. There she joined the team that planned, secured funding and supervised a massive project at Historic Jamestowne that included the excavation of James Fort, which archaeologists had just discovered was actually on dry land and hadn’t been lost to erosion after all.

“It would be a surprise to my grandmother that her granddaughter got to be a part of that,” said Kostelny, an art education major at Longwood, who went on to become CEO of Preservation Virginia in 2001 and held that position until her retirement in 2024. Her grandmother also would no doubt be proud that her granddaughter had a hand in everything that has been and continues to be learned from the excavation and other projects on the 22 acres of Jamestown owned by Preservation Virginia—and of her selection as the recipient of Longwood’s 2025 Distinguished Professional Achievement Alumni Award.

Since the fort excavation began in 1994, more than 3.5 million artifacts have been recovered from the site, said Kostelny, and “it continues to reveal insights into the interactions between Virginia’s indigenous people, English settlers and Africans who came to this continent in the early 17th century.”

The Jamestown Rediscovery project put Preservation Virginia in the spotlight, but as the oldest state preservation organization in the country, Preservation Virginia has impacted many additional historic sites, both directly and indirectly.

“When I became CEO, the organization was in transition and needed to be restructured and reimagined so that it was financially sustainable and relevant,” said Kostelny. “That apparently was a talent I didn’t know I had: How to work with organizations and how to transform them. While I was there, we went from owning 28 historic sites to owning seven, six of which are open to the public. We transferred the other properties to organizations that could care for them more completely. And we changed our approach to provide communities with the skill sets and contacts and tools they needed to preserve the historic sites in their communities.”

Kostelny gave several examples of Preservation Virginia’s influence in helping communities save their important historic sites during her time as CEO:

- Several of the Rosenwald schools, which were established to educate Black children during segregation, including a school in Cumberland County that is fighting a landfill project and raised funds to preserve the school and repurpose it as a community center.

- Shockoe Bottom, the second-largest trading place for enslaved people, which had been selected as the site for a baseball stadium and instead has become a memorial park and educational area.

- Rassawek, the historical home of the Monacan nation, which successfully thwarted plans to locate a water-treatment plant there.

Among the properties Preservation Virginia continues to own and operate are the home of John Marshall, fourth justice of the U.S. Supreme Court who was influential defining the role of the court; a house in Surry County that recent research revealed had been purchased by three freed African farmers in 1886, adding to the story that will be used to educate visitors on events after the Civil War, especially those affecting African American farmers in that region; and Bacon’s Castle, the oldest brick dwelling in North America, built in 1665 in Surry County.

“For Bacon’s Castle we acquired funds to replace the roof and repoint the distinctive brickwork. Things like that are not the sexy part of historic preservation, but these old places have to be cared for and these are the big-ticket items,” she said.

Kostelny discovered her passion for historic preservation in a roundabout way, falling in love with museum work during her graduate studies in art history at the University of South Carolina and then, after a move to Richmond, taking the position at Preservation Virginia when she was looking for a museum job.

“Some people can view history as being very stagnant—that it’s dates and events about the past. But I think when you stand in a building where important, or even mundane things, have happened over the centuries or you stand at an archaeological site last touched by someone 400 years ago, something awakens inside of you and you see that history is very much present,” she said. “These sites are important not only because of what happened there but also how what happened there has influenced things today. In that way, the history contained in historic sites is really dynamic.”

Do you know a deserving Lancer?

Whether they've excelled in their career or had a lasting impact on those around them, consider nominating a Longwood alum you know for one of the Alumni Association's seven awards.