For more than two decades, Beth Macy reported from the front lines of the ballooning opioid crisis in southwestern and southside Virginia as a journalist for The Roanoke Times. From economically depressed rural factory towns to wealthy Roanoke suburbs, she bore witness to the stories of the people who became addicted, family caregivers and health care providers who were among the first impacted and the first to sound alarms about the growing epidemic.

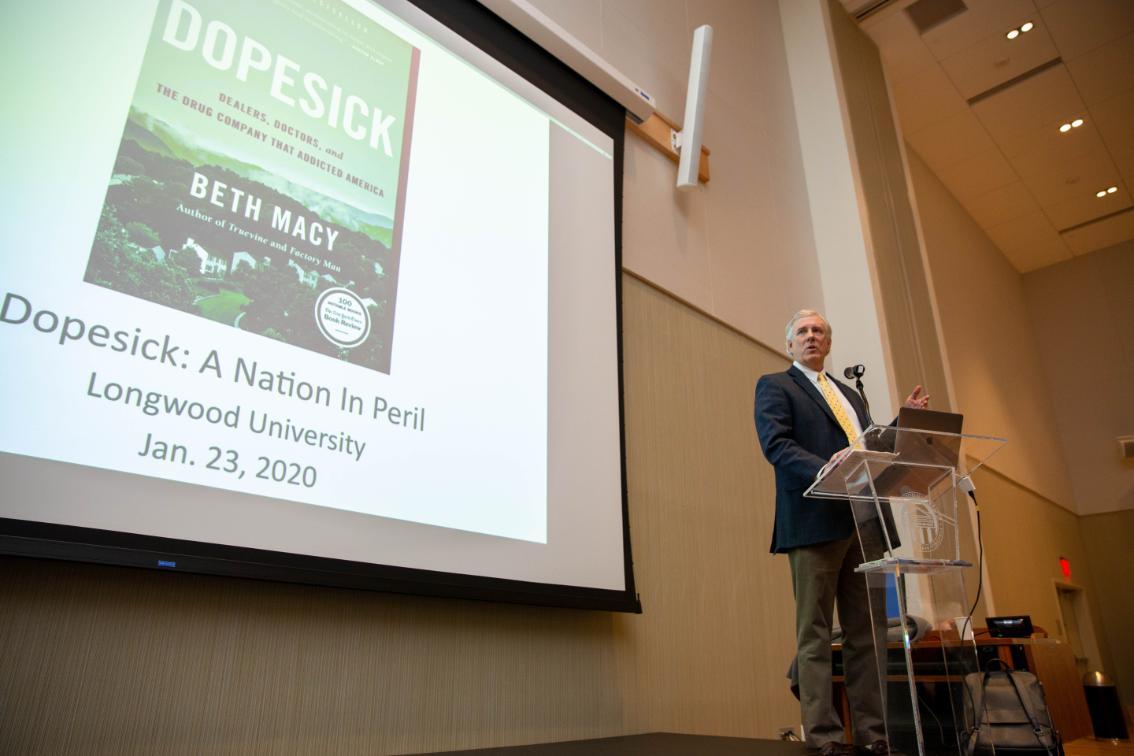

Macy’s reporting and research culminated in her 2018 New York Times best-selling book, Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America. At a President’s Lecture Series talk at Longwood last week, she detailed how her experience telling these stories had transformed her from journalist to activist.

Dopesick is a national book about the opioid epidemic as I witnessed it landing over two decades, set in three communities in Virginia

Beth Macy, New York Times best-selling author Tweet This

“Dopesick is a national book about the opioid epidemic as I witnessed it landing over two decades, set in three communities in Virginia,” she told the large audience, which was a blend of students, faculty, staff and community members.

Macy described her book as a call for action—and the numbers she shared are staggering. Last year 68,000 people in the United States died as the result of a drug overdose, roughly half of which were from opioids. In the past 15 years, 300,000 Americans died due to overdose and another 300,000 are estimated to die in the next five years. She said the epidemic is currently predicted to plateau sometime around the year 2025.

“One estimate says that, with lost productivity, criminal justice and health care costs, lost wages and foster care, this crisis is costing us about a trillion dollars,” she said.

Through her reporting and based on scientific research, Macy has become an advocate for medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which combines behavioral therapy and medications to treat substance-use disorders. She said a common misconception associated with MAT is that it substitutes one drug for another. Instead, medications such as methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone, when used to treat opioid dependence and addiction, relieve the withdrawal symptoms and psychological cravings that cause chemical imbalances in the body.

Macy said while the Centers for Disease Control and World Health Organization believe that MAT should be the gold standard of care, only 20 percent of those who are opioid addicted get MAT. One reason is that medications used in MAT for opioid treatment can only be dispensed through programs that are certified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, although practitioners can apply for a waiver to practice opioid-dependency treatment with approved buprenorphine medications. During the question-and-answer period, one local health care provider said she was in the process of getting that waiver.

Macy argued that the opioid epidemic is festering and growing because it is taking advantage of longstanding fissures in American society and the stereotypes and stigma associated with drug use. There’s a fundamental difference between treating people with Opioid Use Disorder as a patient looking for medical care and treating them as hardened criminals, she told the roughly 250 people in attendance.

“We have 2.6 million Americans addicted to opioids. And as story after story in my book showed me, just putting people in jail isn’t going to make the problem go away,” Macy said. “The moralism around drug use too often usurps the science.”

Macy is also the author of Truevine and Factory Man. Factory Man, which Macy often refers to as Part 1 of Dopesick, came out in 2014, just as the opioid epidemic was gaining national attention and setting off alarms due to record numbers of overdose deaths. Set in Martinsville, Virginia, where in 2015 more opioids were prescribed per capita than anywhere else in the country, Factory Man is the story of a furniture maker in Galax, Virginia, who sues a Chinese manufacturer in order to save his business.

Macy, who left The Roanoke Times in 2014, told the crowd assembled in the Soza Ballroom of Longwood’s Upchurch University Center that most journalists don’t view themselves as activists because their role is to report on facts and educate—not to advocate. But her thinking has changed now, she said, as she embraces her new role as activist.

“I go around and try to get people to change their thinking and to look at the research,” she said. “We need urgent care for the addicted.”

Her next book will focus on solutions to the opioid crisis and telling the stories of the innovators who are thinking outside the box and pushing back against societal norms when it comes to addressing the epidemic.

Some of the things that can help, Macy said, include expanding and improving drug courts and encouraging more people to get out of their silos and look at innovative solutions that fit their communities. One person can make a huge difference, she said, whether it’s by starting a needle-exchange program or seeking to open a methadone clinic.

Macy was introduced by Dr. Kevin Doyle, associate professor of counseling and coordinator of the counselor education program at Longwood. Doyle also oversees Longwood Recovers, Longwood’s collegiate recovery program. The program received a grant last year to help facilitate its growth and efforts to reach more students.

In closing, Doyle thanked the audience for attending and noted the “heaviness” of the topic. But, he said, it is the responsibility of institutions of higher learning to have these difficult discussions, to help facilitate better understanding of social problems and to reach for solutions.

“This drug, this epidemic, really spares no one,” Macy said.