Jacob Spain ’17 has learned a thing or two about the feeding habits of young fish.

The Longwood University student recently spent a lot of time watching bluegill, only a week or two old, feeding on zooplankton, the tiny crustaceans that form virtually their entire diet.

"The fish feed constantly. If there’s food in their tank, they’ll keep eating it," said the biology major from Prince George. "I’ve also been a little surprised by how well they see. Their vision is spectacular."

Their voracious eating habits and keen vision may come in handy. Spain conducted a research project on whether the increase in dissolved organic carbon concentration in freshwater and coastal marine systems—called "brownification"—has affected the ability of fish to see and capture their prey.

"I did various experiments to see if the increase in the brown color of water has any effect on the aquatic food web," said Spain. "I focused on larval fish because, for them to reach adulthood, it’s critical that they be able to find food."

The PRISM program teaches you how to design and run experiments correctly, and how to analyze your data. It’s like a crash course for grad school.

Jacob Spain ’17

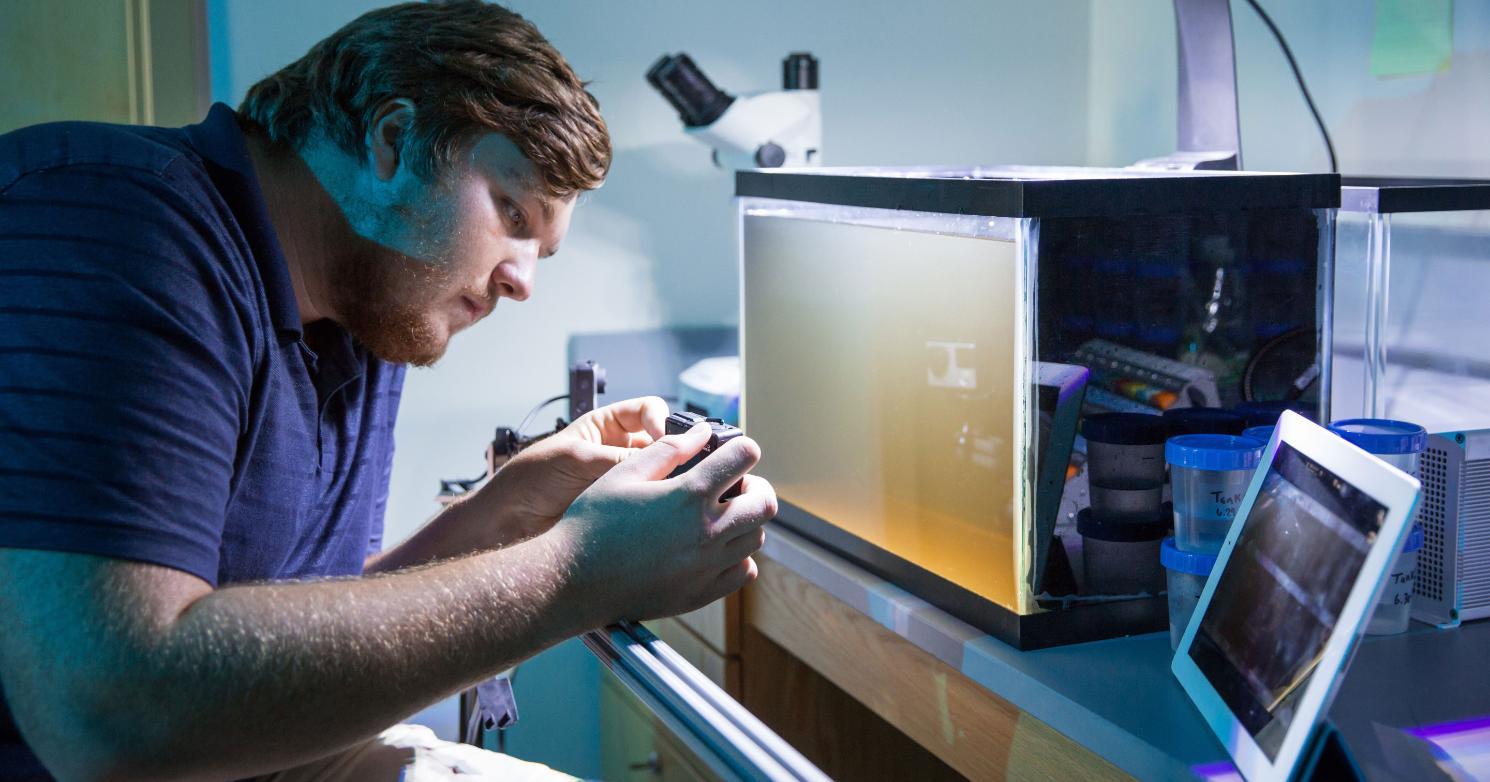

Using two GoPro cameras mounted on a horizontal tripod, Spain videotaped fish feeding in a tank in which the water is manipulated so that it’s variously light, medium or dark brown.

"We’ll be able to tell how far and how fast the fish are moving when they capture their prey," he said. "We want to see how efficiently they hunt their prey and whether there are differences among the three shades of brown water."

Other experiments in the research, part of the PRISM program, also examined the ability of young fish to see and eat zooplankton in tanks with light, medium or dark brown water. This is a continuation of a brownification-related project in summer 2015 that examined interactions between algae and zooplankton, which eat algae.

"Last year we set up tanks with algae and zooplankton, but no fish, for a month and found the dark brown tanks had less algae and less zooplankton," said Dr. Dina Leech, assistant professor of biology, the faculty mentor for both projects. "Then we put in fish for six days and observed that fish in the brownest water tanks did not grow as much—but is that because there is less zooplankton available or because they can’t see the prey as well? That’s what this summer’s experiments tried to figure out."

An avid fisher and kayaker, Spain especially enjoyed collecting the fish and zooplankton for his experiments, which he found at Sandy River Reservoir and a local pond. Spain also enjoyed accompanying Leech in early June to a conference of the Association for Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography, in Santa Fe, N.M., where she presented a paper on their research.

Spain has worked in Leech’s aquatic ecology lab since fall 2015. He plans to attend graduate school and pursue a career in aquatic science research.

"The PRISM program teaches you how to design and run experiments correctly, and how to analyze your data. It’s like a crash course for grad school," he said.