Fingerprints are known to be important clues in solving crimes—but in predicting and preventing disease?

That’s right, says a Longwood University biology professor who played a key role in a study that suggests fingerprint analysis can predict, as early as 17 weeks after conception, who is at risk for developing diabetes, a disease that is estimated to affect more than 29 million Americans.

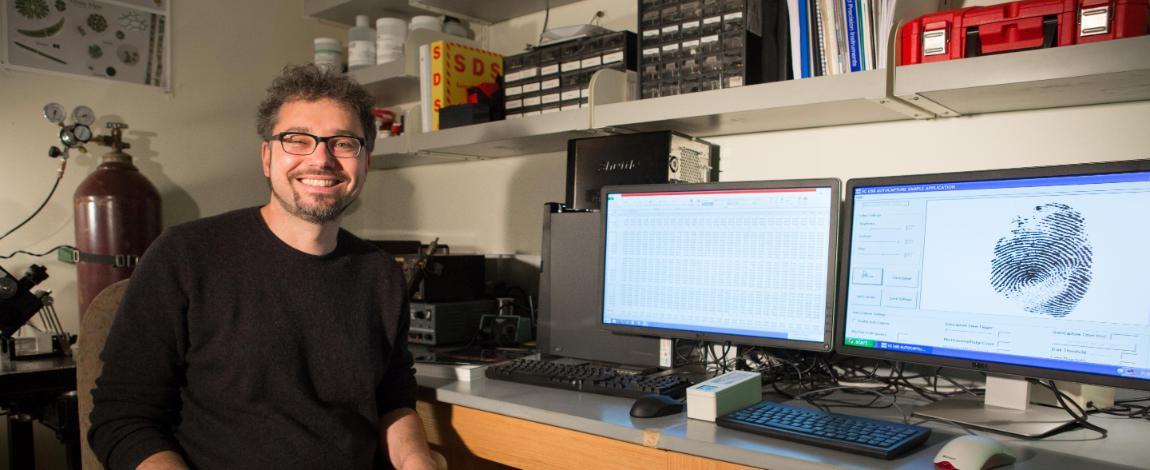

Dr. Björn Ludwar’s role on the research team was to develop an inexpensive and easy way to analyze a person’s fingerprints, which surprisingly can be indicators of health. The less similar the prints on your left and right hand look—the more asymmetric your hands are—the higher your risk might be to develop diabetes later in life. Ludwar’s technique expands on wavelet analysis—the same tool the FBI uses for archiving fingerprints—to check for asymmetry.

"Our findings could eventually lead to the development of a cellphone application to determine the risk for developing diabetes and associated health problems later in life," said Ludwar, coauthor of an article about the research published recently by the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology.

"The problem, especially with Type 2 diabetes, is that typically you are first diagnosed in your early 50s, and the disease by then has already done a lot of damage to your body," he said. "Our most important finding is that we might be able to make a reliable prediction much sooner, creating time for lifestyle changes that prevent this damage."

The built-in fingerprint sensor found on newer iPhones could be used to analyze a person’s prints directly with the phone, or fingerprints could be encrypted and sent to a server to be analyzed, said Ludwar, adding the ring finger is the best candidate for analysis because it usually is the least used and therefore provides clearest prints.

Many of the current tests for diabetes risk involve genetic testing, which is expensive and not easily available to the general public. Other tests work well only a few years before the onset of diabetes when damage to the body might have already occurred, said Ludwar. "The technique we used for fingerprint data proved more reliable for risk prediction than other techniques."

"Our findings could eventually lead to the development of a cellphone application to determine the risk for developing diabetes and associated health problems"

Dr. Björn Ludwar

The study, led by Ohio University (OU) biologyetes professor Dr. Molly Morris, was based on the concept of "fluctuating asymmetry," which maintains that an organism’s genetic ability to cope with environmental stresses is reflected in deviation from perfect bilateral body symmetry. The greater the deviation, the less one’s ability to cope with environmental stress—making it more likely for certain diseases to manifest later in life.

Fingerprints were chosen for the study because, similar to diabetes, they are influenced by both genetics and the gestational environment. Fingerprints form during early gestation—beginning with the thumb at 6 weeks, then "moving down the line" and ending with the pinky at 17 weeks—and thereafter remain unchanged, said Ludwar.

"The use of fingerprints to diagnose diseases, called clinical dermatoglyphics, is currently a very active field of medical research, but to my knowledge we are the first to figure out how to efficiently measure fluctuating asymmetry and show that it might be useful to predict a person’s risk to develop diabetes," he said.

Ludwar’s job was to quantify fingerprint asymmetry of the 340 research participants, about 200 of whom had been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes and another 57 with Type 1. His technique is not affected by the orientation of the finger when the print was taken, and it is much more sophisticated than the old method of counting fingerprint ridges.

In addition to Morris and Ludwar, the research also involved Dr. Jay Shubrook, director of OU’s Diabetes Endocrine Center at the time of the study. Longwood student Mahelet Mamo, a sophomore biology major from Herndon, assisted with the study and is a coauthor of the research article, "."

Mamo, who plans to be a doctor, helped Ludwar with the data analysis. She has worked on several other projects in his electrophysiology lab at Longwood, which more typically focuses on brain functions. A neurobiologist by training, Ludwar conducted research as an assistant professor of neuroscience at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City from 2005 until joining the Longwood faculty in 2014.

Ludwar, Morris and Shubrook are applying for funding to do a larger study and have been granted a provisional patent for their method of using fingerprints to detect the risk of diabetes.