Spoiler alert: This post contains information about the Game of Thrones‘ Season 5 finale.

It’s no secret George R.R. Martin is a student of history—and a well-versed one at that.

Echoes of medieval history can be found in nearly every storyline in Game of Thrones, and Cersei Lannister’s public humiliation on Sunday was no different. Martin, author of the novels on which the show is based, and the showrunners drew from historic medieval French law and medieval literature to create one of the most gut-wrenching scenes on television.

Dr. Larissa Tracy, associate professor of medieval literature at Longwood University, reveals the historical and literary basis for the scene:

In medieval France, adultery was punishable by a naked walk of atonement.

A 13th-century French statute in the Costuma d’Agen, the customary laws of the Agen province, lists public humiliation for both the wife and her lover as the appropriate punishment for adultery. The man and the woman were roped together naked and forced to walk through their town preceded by trumpeters for all to see and sometimes even beaten with clubs.

The point was to destroy someone’s reputation.

Medieval adulterers who were punished by public humiliation lost the one thing that gave them standing in the world. This concept stems from the idea of fama, Latin for reputation or good name. The standing of individuals before the law was often based on their reputations, what others thought of them and how they behaved in public. Crimes had an adverse effect on a person’s fama: The Old French customary law, the Coutumes de Beauvaisis (1283), the Etablissements de Saint Louis (1257), the Counseil a un ami (1253) and the Costuma d’Agen (13th century) all address the issue of good name and notoriety as proof of social standing. Those whose fama suffered through a public shaming like Cersei’s walk of atonement were no longer deemed honorable members of society.

The punishment was centered on women.

The woman was always the center of the punishment. If the man could escape before, or even after, arrest, he could get off without any kind of punishment and his partner had to face her punishment alone. The woman got no such reprieve.

Fate worse than death…or torture?

Contrary to popular belief, medieval adulterers were rarely subjected to violent punishments and torture. In medieval law, the whole point of the walk of atonement was to permanently brand the offender–not with a burn upon the skin, but with a visual performance of the confession–to establish the publica fama. Indeed, a lifetime of shame is a mark that can never be covered.

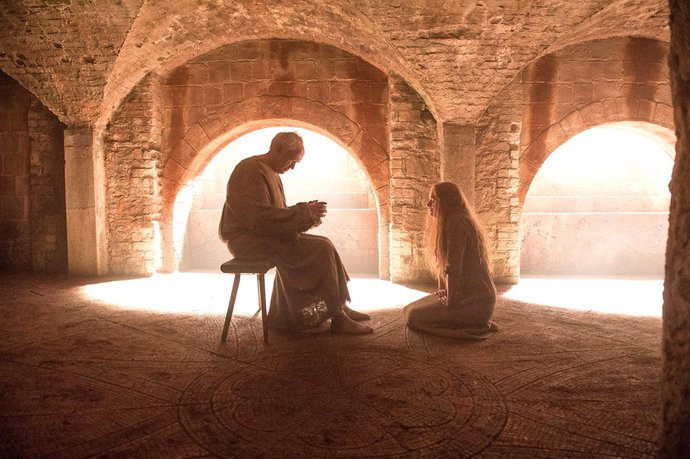

Cersei’s story echoes the most infamous adulteress in literature: Guinevere.

Like Guinevere, whose disastrous liaison with her husband’s best knight, Lancelot (whose name happens to bear a striking resonance to Lancel Lannister), Cersei will suffer from this spectacle more than she realizes. In various medieval tales, Marie de France’s Lanval, Thomas Chestre’s Sir Launfal and Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, Guinevere faces a number of accusations similar to Cersei’s—mostly murder and adultery.

It’s not an unknown role for the Game of Thrones actress.

In an interesting coincidence, Lena Headey, who plays Cersei in Game of Thrones, played Guinevere in 1998’s television miniseries Merlin.

But Lancel isn’t Game of Throne’s Lancelot…that’s Jaime.

In Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur (1471), Guinevere is found guilty of adultery and treason and sentenced to be executed by public burning. She is saved by her love, Lancelot, who charges in, sword swinging. And though Lancelot ends up becoming a religious hermit like Lancel on Game of Thrones, Jaime is more likely Cersei’s Lancelot. It’s just this type of rescue that she envisions—Jaime charging in at the last moment to save her from public indignity. But Cersei’s true Lancelot doesn’t arrive.