On spring and summer mornings, Terry Hudgins ’84 wakes up before the sun, getting outside before the dew burns off the knee-high sea of fescue in the side field of his Buckingham County farm.

Dotted throughout the field are slowly moving cows, filling their stomachs before they retreat to the shade of trees for much of the day.

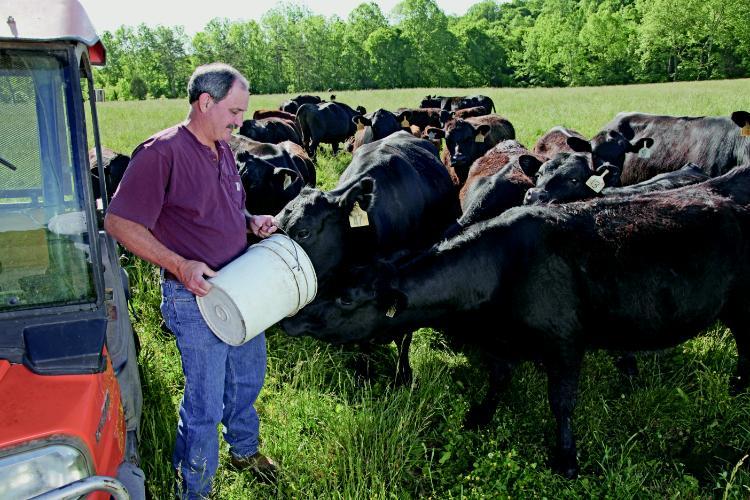

This morning, Hudgins will move his herd of 100 head to a different field, mimicking the bison that moved across the wild American plains a century ago.

“The cattle eat a third of the grass in a field, trample a third into the soil, and we leave a third to go to seed,” said Hudgins. Then we move the cattle to another field. That’s the holistic approach that keeps the cattle healthy and the land rich—the way nature has done it for centuries.”

Terry Hudgins ’84 maintains a herd of about 100 cattle, taking a holistic approach to how he raises the animals and maintains the land where they graze.

Hudgins’ respect for the land and his livestock— as well as his sense of responsibility as a farmer—can be traced back, in part, to an anthropology class he took with Dr. Jim Jordan.

“I learned about past civilizations and how agriculture is the backbone of a community,” Hudgins said. “When the agricultural base is gone, the community fails.”

That broad perspective is complemented by the specialized skills he acquired as a business major, which he calls “a huge part of my farm’s success.”

Hudgins is one of a number of Longwood graduates at the forefront of a movement to keep family farming viable in the 21st century. For some, the way of life was passed down through family; for others, it is a passion they found on their own. But for all, it is a challenge that taps the full range of their experiences and educations—not just science and business acumen, but the holistic skills of imagination, teamwork, persistence and critical thinking that are the hallmarks of a Longwood education.

About 80 miles due east of Hudgins’ farm, Anne Kirby ’69 has spent the last 40 years rising before dawn.

Her family’s 700-acre farm is one of the largest vegetable operations in Hanover County, growing everything from the famous Hanover tomatoes and cucumbers to collards and curly kale. It was a life she never expected, teaching for seven years in Manassas and Mechanicsville before committing to a life as a full-time farmer.

“I knew from the get-go this was something I would love,” she said. “It was hard at first— a lot of things didn’t come naturally to me, and it’s not easy work—but now that we have reached this point, I can watch my son build on what we established.”

Agriculture is a notoriously unpredictable business, with success subject to the vagaries of weather, insects, disease and market forces. That’s where Kirby says her Longwood education has made the difference. As a home economics major, she developed “the traits, abilities and confidence” to meet new circumstances and challenges head-on.

Many farmers don’t fare as well as Kirby and her family.

The number of Americans operating farms is steadily decreasing, down to just 3.2 million farmers in 2012—and that’s at the same time the average age of farmers has risen to older than 58, an eight-year increase over a 30-year period. And perhaps the darkest harbinger of all: The number of new farmers has declined more than 20 percent in the last 10 years.

But there’s more to it than numbers.

Farming sings a siren song to some who simply can’t picture life without it. They speak of the freedom of farming. Of the family legacy they are proud to carry on. Of the fundamental nature of the work. To a person, they can’t put their finger on the exact feeling the work evokes for them. But there’s something about farming, they say. There’s just something about it.

THROUGH THE GENERATIONS

My first job was pulling bad peaches out of a box,” said Cynthia Chiles ’85, with a laugh. “I spent every summer vacation working in a packing house until I got old enough for a driver’s license. Then my job title changed to ‘gopher!’”

If you have been to Charlottesville in the summer, chances are you’ve visited the most well-known of the Chiles family orchards— Carter Mountain. With its incredible vista overlooking the rolling central Virginia hills, the orchard is a popular destination for peach and apple lovers who trek up the winding mountain road to wander through the gnarled trees looking for a perfect fruit. In operation since the 1970s, the operation was started by Cynthia’s parents, but its roots reach much deeper.

“Our first orchards were planted in 1912 in Crozet,” she said. “They weren’t diversified at first, but in the last 100 years we have expanded to several more farms and added several crops—cherries, wine grapes and pumpkins—to go along with our peaches and apples.”

Sarah Chiles ’89, joined the family business after a 27-year teaching career in the Fluvanna County schools. She said her education studies at Longwood prepared her equally as well for her second career.

Sarah Chiles ’89 (left) and Cynthia Chiles ’85 are part of a multigenerational family that started farming in Crozet in 1912. The operation includes three pick-your-own orchards and produces a variety of crops, including peaches, apples, wine grapes, cherries and pumpkins.

“There are a lot of similarities between the field of education and agriculture. Both require extensive amounts of planning and preparation, and both require one to look at things from different perspectives,” she said. “You disaggregate data to make decisions on how to proceed.”

Chiles produce is sold in grocery chains around the world, but it’s still a family business. Cynthia and Sarah are part of three generations of Chileses who work the orchards now, including their parents and their brother and sister-in-law. All are helping the next generation find their way forward as they become interested in working the orchards.

That generational aspect is a powerful part of farming. There’s a great deal of pride in hanging a “Virginia Century Farm” sign at the end of a driveway, signifying the land has been in continual operation for at least 100 years. Anne Kirby’s Mechanicsville farm is one of those—though she has been working the land for only four of those decades.

“My husband and I are very proud that our son wanted to build on the success that we have accomplished,” said Kirby. “It’s great to see your children develop a love for the land that you worked for years, and, now that the grandchildren are showing an interest, there’s a legacy developing. That’s what farming is, at least to me: family.”

AN AMERICAN ICON RETURNS

Kim Evoy Bryant ’86 spent much of her career building a successful software development company with her husband. Born in New Jersey, she was as unfamiliar with her husband’s Nelson County roots as she was with the practice of farming, but life in the country eventually called. With it came the opportunity to corner the market on an American icon that all but disappeared for generations: chestnuts.

The nut, iconic enough to open that timeless Christmas song, disappeared from American life in the early 1900s. Blight largely removed chestnuts from grocery store shelves and the tree from the backyards of many homes. Today, 90 percent of chestnuts eaten in the United States are imported.

The Bryants are working to change that.

Helping to resurrect the American chestnut is a labor of love for Kim Evoy Bryant ’86, who runs an orchard of blight-resistant trees in Nelson County with her husband. Their company, Virginia Chestnuts, sells nuts to restaurants and grocery stores in Charlottesville, Richmond, Fredericksburg and Washington, D.C.

They planted their first blight-resistant trees in 2009, the beginning of Virginia Chestnuts. Sixteen hundred saplings later—all planted by hand—their nuts are available in restaurants and grocery stores in Charlottesville, Richmond, Fredericksburg and Washington, D.C. Their biggest challenge: convincing people to try them.

“We have had to re-educate the market on chestnuts,” said Bryant. “Most people in the United States have never had a chestnut, and that’s a shame because they really are very good. So we’ve put together partnerships with breweries and restaurants to get the word out. And, of course, each fall we have chestnut roasts at local gathering spots.”

An elementary education major at Longwood, she said having the confidence to try something different is a direct result of her experience with faculty member Dr. Robert Gibbons, who “challenged me and was a great example of seeing things from different perspectives.”

“Chestnut farming is definitely not in the mainstream, but, by looking at agriculture from different perspectives, we believe this is a good long-term business model,” she said, adding that she and her husband have established a growers group in Nelson County with five other farmers.

Even so, Bryant cautions against quitting your day job. Farming, after all, is a difficult profession to sustain.

CATTLE CALL

That’s a problem that Terry Hudgins has wrestled with for years, and he’s taken a scientific approach to solving it.

“I realized that effectively I’m a grass farmer,” he said. “The advantage to raising cattle is that grazing can be done with sun, grass and rain, and I use the cattle to convert solar energy into protein. That’s the basis, and places like the Savory Institute have developed holistic management techniques to mimic the high-intensity livestock grazing patterns that naturally developed to keep the grass growing and the cattle fed. That’s how you consistently make a living despite market fluctuations up and down.”

The Hudgins herd is hormone-free, a commitment to the health of the animals that graze on his land. With the demand for beef rising, many farmers have turned to hormones to spur growth in their cattle to get to market more quickly. The health risks associated with that surge of hormones is negated by regular antibiotic use—all of which affects the quality of the meat.

“I want to put the best meat I can on people’s tables,” said Hudgins. “That, to me, means knowing that the cow was raised humanely and treated properly—not artificially inflated so I can make more money at auction. I’ve also adopted low-stress practices when handling cattle. I spend a lot of time with the animals, building up trust and a relationship that gives them a better life.”

KEEPING IT LOCAL

In the last several decades, a local food movement has taken shape as consumers have sought out farmers who sell directly to them or through regional distributors who put a premium on sustainable, healthy food grown locally. Today, almost 10 percent of farms are marketing foods locally—and finding that being part of the movement is a way to stay in business for the long term.

The Kirby farm produces nearly a quartermillion boxes of produce each year, selling some to Produce Source Partners and Local Food Hub—two local distributors that deliver the Mechanicsville vegetables to tables in central Virginia.

“We like the idea of our produce being distributed locally,” said Anne Kirby. “The number of people who want to be familiar with the places their food comes from is growing.”

A big part of the local food movement is marketing directly to consumers. Sales of locally grown food sold directly to customers have charted double-digit growth in the last 15 years, a testament to the increasing popularity of the movement—which has become a $6 billion business.

"So many of our customers like to smell the orchards and touch the fruit they pick—it connects them to the food in a powerful way."

CYNTHIA CHILES ’85

It wasn’t always that way. In the late 1970s, when Cynthia Chiles’ parents opened their Carter Mountain Orchard to self-pickers, local food was a fledgling movement popular among only small pockets of people. But Chiles, who developed her business acumen at Longwood, and her family had a vision that proved true.

“They didn’t know what to expect,” said Chiles, “but that first season became so popular among the people around Charlottesville that a new part of the business came into being. Now three of our orchards are open to people coming to pick fruit, and it’s really become the beating heart of Chiles orchards.”

Selling direct to consumers is a major part of the operation that annually produces several hundred thousand bushels of fruit each year—and it keeps the family grounded. So many of our customers like to smell the orchards and touch the fruit they pick— it connects them to the food in a powerful way,” she said. “There’s nothing like eating a ripe peach picked straight off the tree.”

IN THEIR BLOOD

Though many farmers can’t describe the exact feeling they get when they are working the land, many of them know it’s in their blood.

“My family has been farming for generations,” said Sam Bacon ’05, whose father, Dr. Frank Bacon, is a longtime economics professor at Longwood. “I’ve been working on a farm since I was 6 years old and always knew there was nothing I’d rather be doing. That doesn’t mean I’d never have another job—but my heart would always be in farming.” The things he learned at Longwood have helped him stay where his heart is.

“My business education taught me how to be a leader and to work with all types of people, whether it is someone who is helping me on the farm or a government official who is auditing me,” he said.

In addition to the crops he grows to support his family, Sam Bacon ’05 (above) uses his agricultural acumen to create a gleaning garden. Last year, he and 84 church members picked 4,500 pounds of produce to donate to needy families in their Lunenburg County community. (below) Anne Kirby’s family runs a 700-acre farm that is one of the largest vegetable operations in Hanover County. The 1969 Longwood alumna is proud of the ‘Virginia Century Farm’ sign on the Kirby Farms property, which signifies the land has been in continual operation for at least 100 years.

Bacon’s love of farming led him to use the skills he developed growing soybeans and tobacco with his uncle to start a gleaning garden—a vegetable patch that he harvests and gives away to needy area families.

Last year, he and 84 church members picked 4,500 pounds of fresh produce to donate— everything from corn to cucumbers to squash.

“This is a way for me to give back to the community that I love,” he said. “There are a few families that I grew up with who are also farmers, and it’s hard to tell us apart— we really are one big family. That’s pretty special.”

Like Bacon, Hudgins felt the call of the land from a very early age.

“The first time I fell in love with farming I was 5 or 6 years old,” he said. “I was standing next to a field, and these grazing cows came up to the fence where I was. I watched them and told my mother I wanted to be a farmer. After that, on every report card I had where they asked you to put down what you wanted to be when you grew up, I wrote ‘farmer.’ I guess I’m one of the lucky ones who got to realize his dream.”

About the Author

MATTHEW McWILLIAMS

PHOTOS BY GUY CRITTENDEN