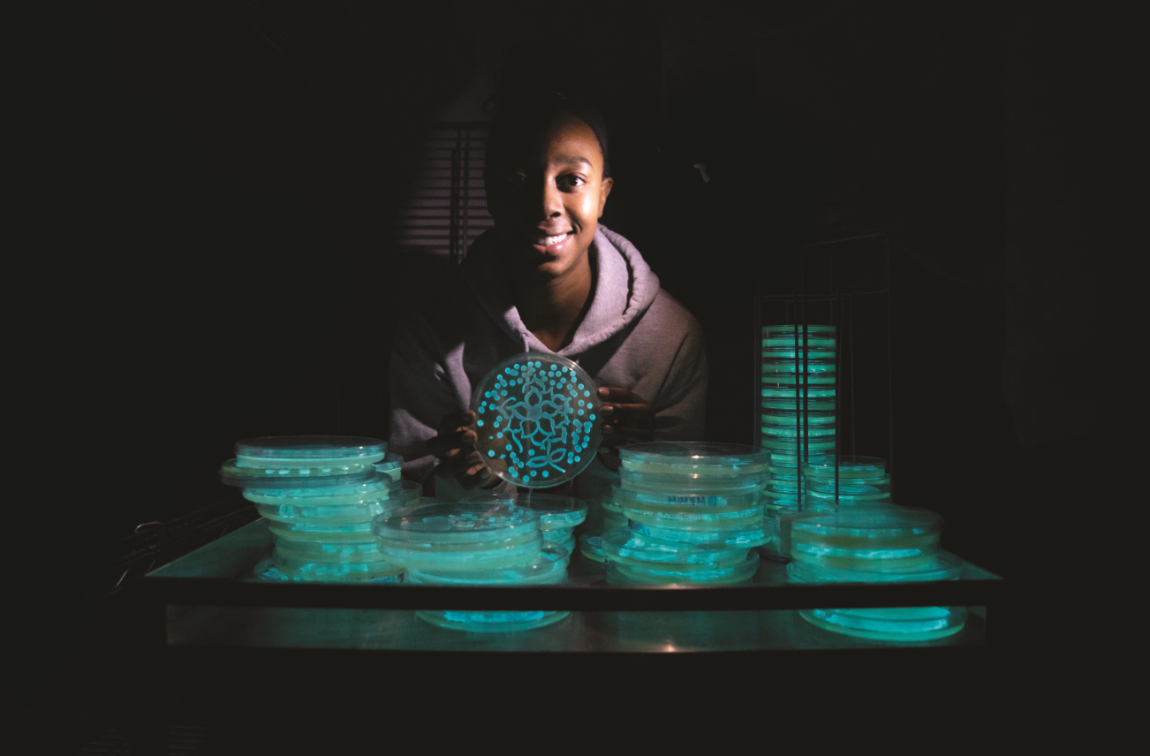

Sitting in a biology laboratory on the second floor of Chichester Hall, Kamarin Bradley ’19, a graphic design major, carefully pulled a sheet of aluminum foil out of her notebook. On it, she had carefully cut out a stencil, a minion from Despicable Me hollering the word “BIO!”.

After she fit the foil into a Petri dish with the help of nearby Tori Acosta ’19, a biology major, Bradley took a paintbrush and began dabbing clear liquid onto the stencil, creating an invisible piece of art.

It wouldn’t be invisible for long—at least not at night.

The project is a collaboration between Dr. Denis Trubitsyn’s upper-level microbiology class and Lauren Rice’s art class titled, aptly, Introduction to New Media.

New media indeed: The clear liquid that Bradley and Acosta carefully painted onto the bottoms of their Petri dishes was teeming with bioluminescent microbes—scientific name Photobacterium leiognathi strain KNH6— glowing bacteria that in just a few hours would begin to emit a soft blue-green light, revealing the pattern the students had created.

“Welcome to our interesting adventure,” said Trubitsyn, assistant professor of biology who initiated the collaboration.

Many of the students’ artworks adopted a Longwood-based theme—a rotunda, Lancer logo or CHI symbol—but many of Rice’s students lifted images from their sketchbooks: intricate drawings of flowers or characters that required delicate strokes to encourage the luminescent bacteria to multiply and glow in perfectly straight lines.

‘Art, as in science, is often a collaboration.’

LAUREN RICE, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ART Tweet This

“Art, as in science, is often a collaboration,” said Rice. “We share ideas and work together. There exists a whole history of ephemeral art— that which is made to not last for a long time. With this collaboration, we have about three days to enjoy the glow of the artwork before it disappears.”

As the microbes consume nutrients in the bottom of the Petri dishes, they emit the light, which can only be seen in pitch-black rooms. Once the nutrients are gone, the bacteria stop glowing.

“These bacteria are fascinating,” said Trubitsyn. “They come from ponyfish, found in the Indian and Pacific oceans, and have a really interesting symbiotic relationship. The bacteria get nutrients from the fish, and live in a special organ in its belly where they shine light downward, effectively reducing shadows that reveal the ponyfish’s location to potential predators. These types of relationships are very important in nature, and, of course, we are echoing that same collaboration with art students in the classroom."